“Mastering the gray areas is to doing business in China what political correctness is to corporate America: MANDATORY!”

You wouldn’t expect to survive in an American boardroom while completely ignoring the unwritten social codes of conduct. Yet Westerners routinely parachute into China expecting success while remaining delusional about its gray-zone operating system.

This ignorance creates a false sense of leverage. It’s foolish to assume any overt strength translates to bargaining power in China. Even if you are Jensen Huang, whose company controls 90% of the silicon driving the next industrial revolution, you must face China’s reality: It can wait. China has infinite patience, and it has “invisible hands” actively guiding its indigenous industries to replace you.

China also has more of what we lack: a gigantic, highly skilled, educated, and trained workforce that doesn’t feel entitled, isn’t chasing the money, and is willing to work harder and longer than their Western counterparts.

There is good news: this immense pool of talent is ready and eager to join your team. But this brings us to the ultimate leadership dilemma that pinpoints exactly why so many Western companies eventually downsize or withdraw from China: You cannot lead a “gray zone” workforce with an absolutist, black-and-white mindset. Western leaders come up short because they don’t master managing the different shades of gray across China’s business landscape.

The Maddening Vagueness

Geopolitics and statecraft are composed of “strategic ambiguities.” The equivalent within China is the maddening vagueness with which most Chinese staff answer direct, unambiguous questions from their Western managers. Yes, it’s cultural. But it is also tactical and conditional.

As an American, I have learned that when I am frustrated by their lack of specificity and accountability, it is a clear signal that I am asking the wrong questions. And until I adjust the fundamental nature of our dialogue, I will remain stuck in an impasse.

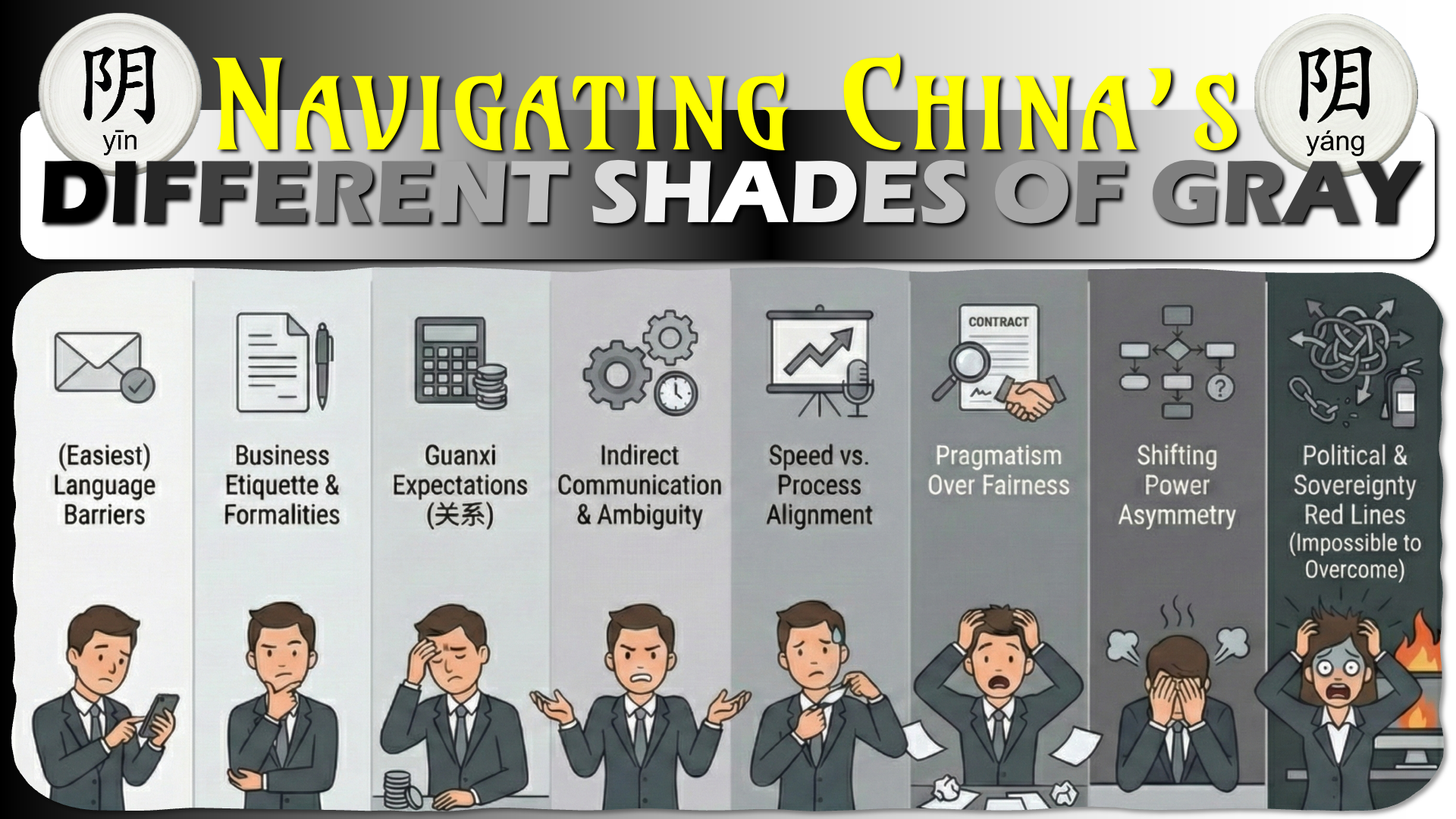

We’ve discussed HOW THEY OPERATE (Guānxì 关系) and WHAT THEY CONSIDER (Lìyì 利益). Now is the time to reimagine WHERE THEY OPERATE.

I describe “the where” as an area that has infinite shades of gray.

Western business culture values clarity: rules, processes, and transparency.

To our Chinese counterparts, however, an obsession with this “world-class” method is humorous and naive. They wonder, “Why would anyone deliberately speak in such a rigid manner as to cut off all pathways to greater prosperity?”

To get things done in China—especially when roadblocks appear—you must understand the practical application of “Yīnyáng (阴阳) thinking.” It isn’t some ancient Chinese philosophy emphasizing balance. In our analogy, it is the pragmatism of not becoming the nail that gets hammered down. It’s the mentality of shared responsibility, and the practicality of positioning a Face-saving off-ramp in case things get worse.

The Ethical Gap

Each of these intuitive Chinese behaviors is rooted in their culture, but what’s natural for them rarely conforms with our ethical guardrails and moral scruples. For example, in the West, we assume that “under the table” payments are bribes. Yet we often fail to acknowledge the duplicity of our own hypocrisy and the corruption common to our political system. There’s a reason that we say, “It takes money to make money.”

“In China, clarity is rarely the goal, but plausible deniability is the rule.”

Now that a picture is beginning to form, the million-dollar question is: “How can I condition myself to flourish in this environment?”

Unfortunately, there are no simple answers because it is generally impossible to teach an old dog new tricks. That said, to rehearse your future success in the Chinese arena, begin with these China commandments:

- Nothing is right or wrong because everything depends on something or someone else.

- Every commitment is fungible because Lìyì Guānxì is dynamic and constantly evolving.

- Chinese people never “say what they mean or mean what they say” because the purpose of communicating is to give and receive Face.

In Chapter 2, we analyzed their internal Lìyì (利益) calculus — the perceived personal benefits behind every decision. Chapter 3 builds on this by showing how Chinese people manage the contradictions that naturally emerge from those calculations.

Next, we’ll reconcile the Chinese definition of trust (Xinrèn 信任, Chapter 4), its relation to truth, and the ramifications when one side defaults-to-trust while the other defaults-to-skepticism in Truth-Default Theory.

Interested in these topics? My latest book, Speak Less, Guanxi More, is now on sale, but I’m still giving away the complete 114-page PDF and Flipbook for free.

Leave a Reply